The following was submitted by Audio Visual Metadata and Training Data intern, Jordan Errico.

For the archivist, corrupted or damaged materials are more than just a workflow headache—the potential loss of information is a setback to cultural or historic conservation. At the same time, insight may still be found in the process of corruption. As an intern working for GBH and the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, among other roles, I am responsible for the digitization and cataloging of a large audio CD collection. Having worked previously at more privatized archives and commercially focused vendors, I am ecstatic to have had the opportunity to work with a public media organization. Author and audiovisual studies scholar Vincenzo Estremo says we must expand the notion of archives “from the idea of a physical storage space that preserves objects and documents, [or] a virtual archive of data collections accessible through computer screens,” and position archival materials so that they may be fully “engaged in reinterpretations of history, along with a political dimension where archives are invested with issues of accessibility and power.”1 The role that public media offers to archives is that of empowering the materials in archival collections to engage discourse through public access.

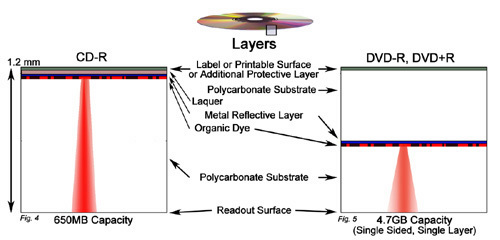

Optical media is fickle, and the lifespan of a disc is finite if stored improperly. Oxidation, degradation, and physical damage create unique audio distortions to data stored on a disc, threatening the complete loss of information. The physical makeup of a disc varies; however, it usually consists of a label or protective layer, a reflective metal and dye layer, and the polycarbonate base. We have largely been working with CD-R type discs, which the Northeast Document Conservation Center explains have “a separate data layer made up of organic dyes. . . sandwiched between the polycarbonate substrate and the metal reflective layer.”2

Layers of an optical disc3

In our work, we have occasionally found discs that refuse to transfer, producing corrupted files with crackling roars of audible distortion. Many of these discs had a common denominator: paper disc labels. Although the exact nature of why these paper labels might cause problems to arise during transfer varies, and the information I reference here is often anecdotal—found on enthusiast forums or online archivist groups—there is a general consensus that poorly made labels may throw off the balance of a disc as it reads in a drive, glue has the potential to strip away data when it dries, causing labels to lift; and printed dyes may cause chemical degradation. Of course, proper storage can go a long way to keep things intact, but the layers of an optical disc are so tightly connected that interference with one may introduce disruptions to the other.

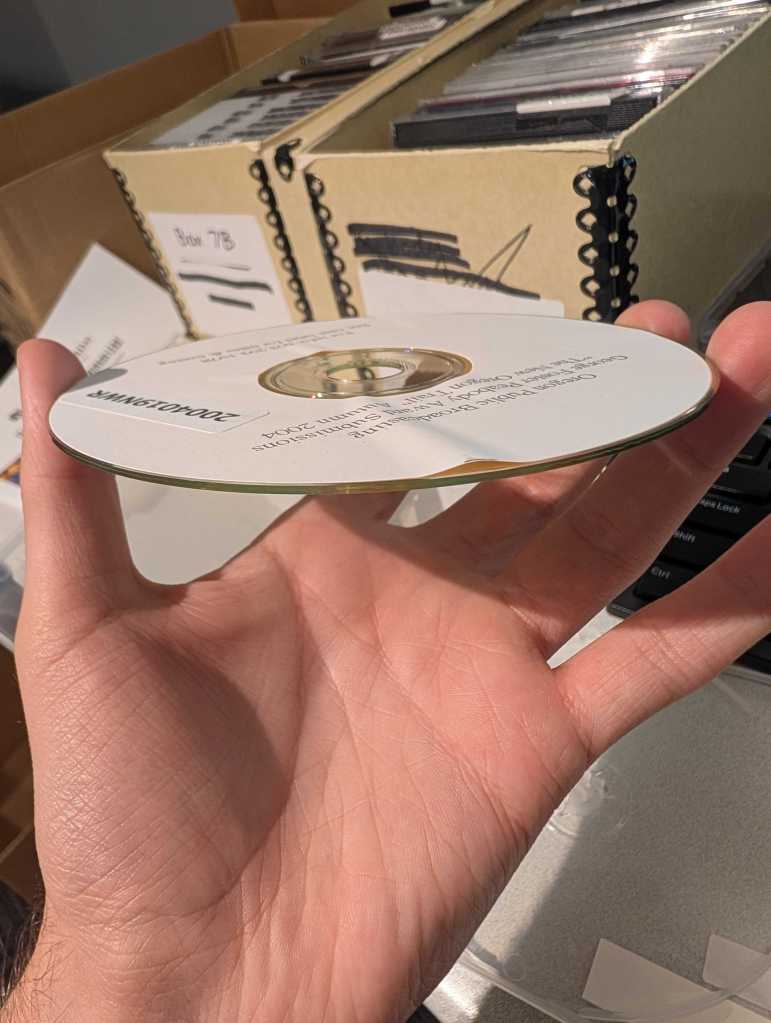

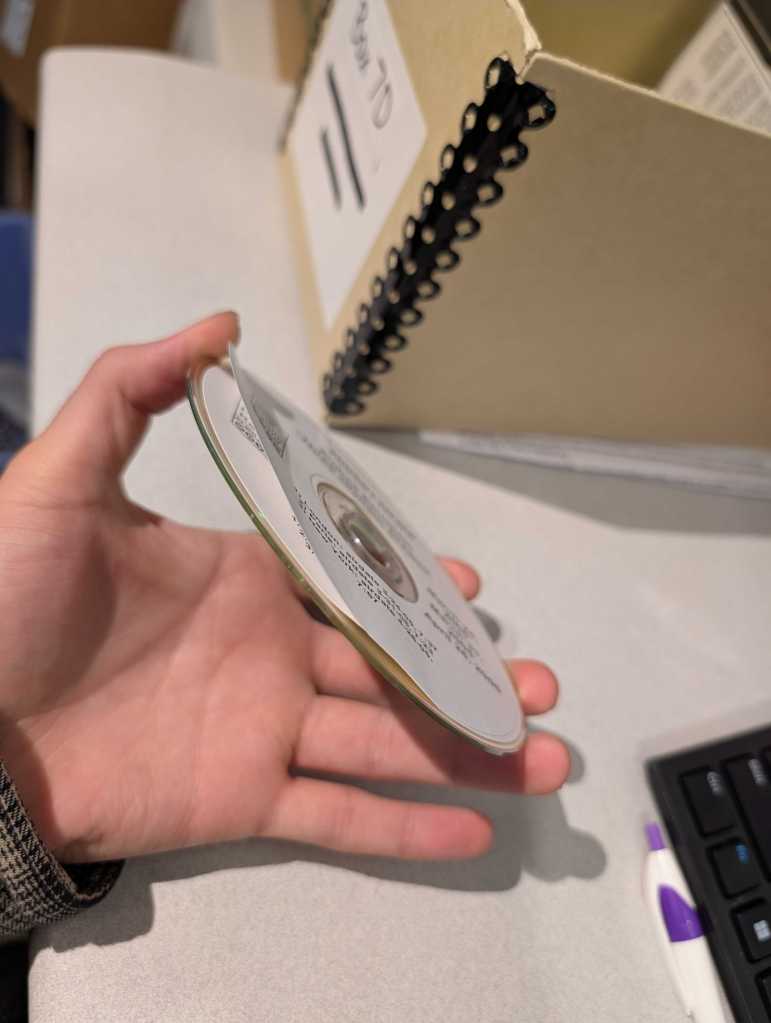

Examples of paper labels we found that are poorly adhered to their discs

Examples of paper labels we found that are poorly adhered to their discs.

Out of 36 discs we found with paper labels, 28 either failed to transfer or encountered significant transfer errors (that’s a staggering 77%). Some had labels which were glued on—over time, that glue dried and caused the label to lift away from the disc. We weren’t able to transfer these discs for fear of what would happen when inserted into our disc drive without fully removing the label. Others spent hours transferring just to inevitably fail in the drive—those that succeeded occasionally produced incomprehensibly distorted audio. Although these discs were only a small population within the nearly 900 we digitized this semester, knowing that these discs contain stories and diverse teachings from an exhaustive list of inspiring radio programs makes it hard to let go when they fail. The initial inklings of disappointment, and admittedly frustration, were not easy to brush off. My colleague has been creating an alternative workflow to re-transfer these discs and copy them onto new CDs, so there is hope for their preservation, but the issue has stuck with me. I am certain that insight can be taken away from these discs in the event of their corruption, and perhaps this provides new ways of listening to the information these CDs offer in their degradation, not in their data.

In his book Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance, the sound artist and author Brandon LaBelle suggests that “sound and listening [put forward a] dynamic framework from which to interrogate ‘the surface of the visual world.’”4 Moreover, the ways in which “[s]ound works to unsettle and exceed arenas of visibility by relating us to the unseen, the non-represented or the not-yet-apparent,” might actually mobilize “as a structural base as well as speculative guide for engaging arguments about social and political struggle.”5 It is not just the effects that sounds produce, but primarily the sound as an object and the context under which it evokes sound or is created that he is interrogating and relating to larger social and political conditions.

Distortion often has a negative connotation, and distorted audio does not necessarily make for an enjoyable listening experience. Artists, especially rock musicians, may specifically seek out distortion for certain tones and effects, but in an audiovisual archive, distortion is typically frowned upon—distortion here means loss or corruption. From this perspective, these unwanted sounds are what the filmmaker and theorist Hito Steyerl might describe in her essay In Defense of The Poor Image as ‘poor images’, the wreckage of dying media formats, or corrupted files. In the same way that LaBelle expands our conceptions of sound to include surrounding information, Steyerl argues that “[t]he poor image is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence.”6 Although a corrupted disc might no longer contain information pertinent to its original recording, by undergoing corruption, it “recovers some of its political punch and creates a new aura around it. This aura is no longer based on the permanence of the ‘original,’ but on the transience of the copy.”7 The way in which media circulates produces a sort of reposturing in its movement from start to end.

Technically speaking, author Alex Case explains in his book Sound FX: Unlocking the Creative Potential of Recording Studio Effects that distortion occurs when “[w]hen the shape of the output waveform [of an audio signal] deviates in any way from the shape of the input.” The deviation of a waveform can occur under a complex array of circumstances. Distortion exists audibly, in what LaBelle describes as the realm of the overheard—distortion is heard, noticeable, and yet created through invisible or unheard voices, conditions, and movements. The overheard explores “relations based on interruption and the noises that often impinge onto” how we listen or speak, it is the encounter between what we hear and the unheard conditions behind that.8

In the case of our troublesome discs at GBH, it seems more likely that these were conditions enabled from the point of their manufacturing to degradation during their long-term storage. Even though there is a directly tangible proponent of this specific issue—paper disc labels—as I continue to find discs with stories and content rendered inextricably silent by audible distortions, I want to propose that care must be exerted in examining the surrounding environments which created that silence. What circumstances occur that render an originally pristine audio recording completely incomprehensible? What silent movements can be traced to the conditions under which a disc, or any archival object, is kept or stewarded? Was a disc manufactured with nefarious intentions—a cheap means of quickly storing information without care for its posterity and longevity? In that same line, why might one recording be placed onto a ‘higher’ quality disc than another? It’s in this practice of having a conversation with corrupted materials that we can begin to understand the conditions of their existence, and grapple with the ways in which distortion also produces silence. We cannot create better practices for conservation without questioning why certain things are kept and cared for and why others are left to degrade. Moreover, we must be brave enough not to abandon corrupted materials as mere failures, but to listen to their offerings, and finally ask: why is a sound corrupted, what unheard movements create distortion, and what leads to silence?

- Vincenzo Estremo, “The Unpredictable Potential of Archives,” Droste Effect (2016). 13. ↩︎

- Northeast Document Conservation Center, “Inherent Vice: Optical Media”. ↩︎

- Council on Library & Information Resources, “Care and Handling of CDs and DVDs: A Guide for Librarians and Archivists, Disc Structure.” https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub121/sec3/. ↩︎

- LaBelle, Brandon. Sonic Agency: Sound and Engagement Forms of Resistance, Goldsmiths Press, 2018. 1-2. ↩︎

- LaBelle, Brandon. Sonic Agency: Sound and Engagement Forms of Resistance, Goldsmiths Press, 2018. 1-2. ↩︎

- Steyerl, Hito. In Defense of the Poor Image, E-Flux, 2009.

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/. ↩︎ - Steyerl, Hito. In Defense of the Poor Image, E-Flux, 2009. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/. ↩︎

- LaBelle, Brandon. Sonic Agency: Sound and Engagement Forms of Resistance, Goldsmiths Press, 2018. 18. ↩︎